Security and billing concerns over Internet access

Hey there! In this post I’m going to talk about the security concerns I encountered when designing the main backend and frontend of the application (especially the frontend part which allowed user input).

Prepared statements to prevent SQL Injections

Not much to talk about this, it’s been known since forever that prepared statements prevent SQL Injections: they allow an application to precompile SQL statements before executing them with actual data. In other words, using them allows us to separate the actual SQL Logic from the data.

Billing: calls to AWS Secrets Manager

The backend will access the database everytime a user submits the form to subscribe from the frontend and a call will be made to Secrets Manager, to retrieve username and password to access RDS, every time a query needs to be done to the database. This is quite impractical and risky, since 10.000 API calls cost $0.05. If an attacker is somehow able to bot my website and easily make milions of calls to the Secrets Manager API, my bank account would be (slowly but surely) drained.

To put remedy to this, a single call to the secrets manager will be made at the start of each ECS Task or Service and the credentials will be saved as environment variables. Secrets rotation will be handled too: if the connection to the database fails, the exception will be checked and if the saved credentials are expired, they will be retrieved once again.

Billing: RDS Storage

AWS Free Tier offers 20 GB of storage per month, if an attacker is able to somehow fill my tables and store 20 GB of records, I would incur in extra costs.

To solve this, I will limit the subscribers table to at most 15 records (for now I won’t be expecting much subscribers).

The manga_releases table doesn’t need adjustments, since an attacker has no way to access that.

The subscribers_subscriptions table doesn’t need adjustments too, since a subscriber can subscribe to at most M predefined manga titles, so the maximum number of records I will have is S * M, where S is the number of subscribers and M the number of manga titles that can be tracked through the application (3 as of now).

The alerts_sent table doesn’t need adjustments either, there are only 3 predefined alerts that can be set, so S * M * A is the maximum number of records I will have, where S is the number of subscribers, M the number of manga titles and A the number of alerts to be sent (3 as of now).

1. Application-Level Enforcement

Just a simple function in my application code to check the current number of subscribers before allowing a new one to be added.

2. Database-Level Enforcement with Trigger

This is a bit trickier but nothing too fancy, just a trigger that prevents insertion when the limit is reached.

Minimal permissions for the ECS instances

Since ECS instances are accessible by the whole internet I need to make sure that they have minimal permissions, just the ones for the resources they actually need to function.

Change Flask into a production server (Gunicorn)

The title is quite self-explanatory, Flask is just a development server, Gunicorn is more secure and has better performance, so I’m going to switch to it before finally hosting publicly.

Access to the S3 Bucket only through the Cloudfront CDN

This is pretty straightforward: I don’t want everyone on the internet to be able to access the S3 bucket on which I’m statically hosting my website, I will make it so that only the CDN can access it. I’m using Origin Access Control and I’m blocking ALL public access on the S3 bucket.

Publicly accessible repository

1. Github Actions: Secrets

GHAs secrets shouldn’t be a problem, since I don’t have hardcoded credentials in there because I’m using OpenID Connect to access resources in AWS.

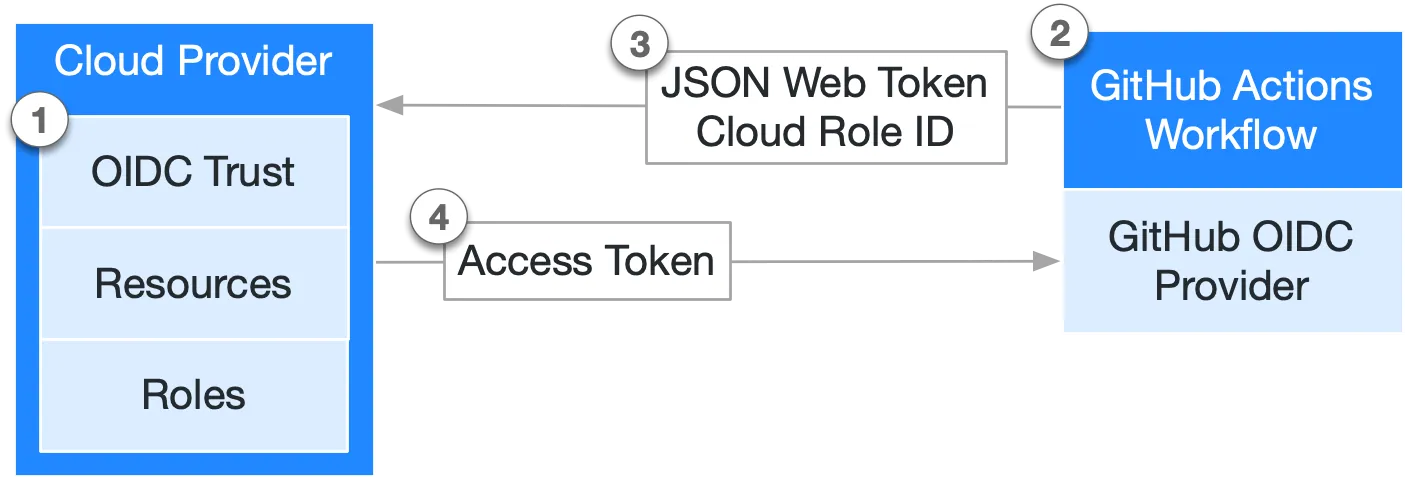

2. Github Actions: OpenID Connect

For this one I need to make a more thorough analysis, to check if making the repo public could result in security concerns: the documentation states that

For this one I need to make a more thorough analysis, to check if making the repo public could result in security concerns: the documentation states that

Before granting an access token, your cloud provider checks that the subject and other claims used to set conditions in its trust settings match those in the request’s JSON Web Token (JWT). As a result, you must take care to correctly define the subject and other conditions in your cloud provider.

so I’m quite interested in the subject field and how the JWT is composed.

- The JWT cannot be crafted, since it’s signed by GitHub OIDC Provider and then that sign is verified by AWS before granting the Access Token, so I can say that I’m secure in that way.

- The

subjectof the Trust Relationship is"repo:aloilor/MangaAlertItalia:ref:refs/heads/main"and it’s correct, it means that AWS will grant the Access Token only to requests coming from workflows from that specific repo and branch.

Ideally anyone should be able to create Pull Requests to main, so I need to be extra careful in defining what triggers my CI/CD pipelines. The only pipeline that actually could be a problem is the Terraform one, since at every PR to the main aterraform plangets executed, but theplancommand doesn’t really affect the cloud infrastructure, so I’m safe here too:terraform applyis executed only when pushing on the main branch, and that can be done just by the repository owner.